What is the purpose of a question? To come up with a correct answer? Or should there be something more?

What if we used questions to come up with more questions? What if our purpose for asking questions was to extend the curiosity of our students rather than just come up with a correct answer?

Asking questions has become a tool for us to focus on and master difficult tasks, especially as we approach the logic stage with our children. But how can we ask powerful and meaningful questions?

Earlier in our homeschooling journey, I realized that many of the questions I asked were limited. Most of my questions were not to challenge a student to wrestle with an idea. My (unintended) goal had been to rush through and finish this question so that we could rush through and finish the next question. The end result was the answer, not the discussion. And yet I enjoyed those moments when our 6th grader would ask a question that challenged us to think harder through something together – and I treasured the time we spent in the dialogue that came as a result. I desperately wanted my children to have inquisitive spirits and to use that to train them to become analytical thinkers! There’s such joy in allowing our children’s natural tendencies towards argument to open a door for thoughtful, adult conversation.

The first canon of rhetoric is invention. It is a time of exploring ideas, asking questions, determining pros and cons of a situation, and general brainstorming. You can explore pretty much in topic or idea by using the Five Common Topics (or or tools of inquiry) which consist of:

- Definition. Questions of definition help the speaker or writer to define the topic discussed. (What do you mean by this topic or idea?)

- Comparison. Questions of comparison help you determine similarities and differences between this idea and that idea. (How is this idea or concept similar to or different from this other idea/concept?)

- Relationship. Questions of relationship determine causes and effects. (What happened before? What happened after?)

- Circumstance. Questions of circumstance lead to connections between the idea and what else was happening during the same time. (What was going on at the same time but in a different place?)

- Authority/Testimony. Questions of testimony provide insight from eye-witnesses or experts on an idea or situation. (What does this “authority” say about this topic or idea?)

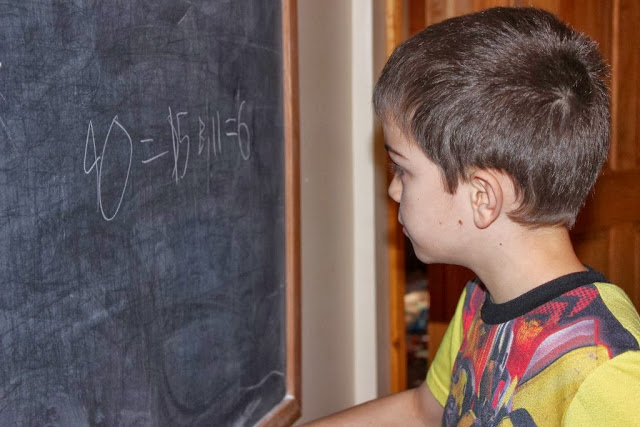

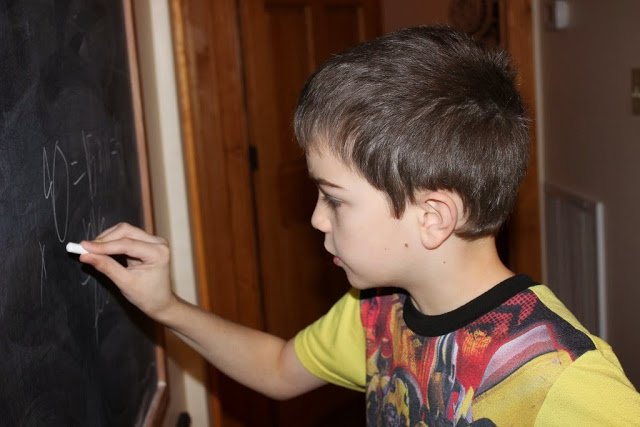

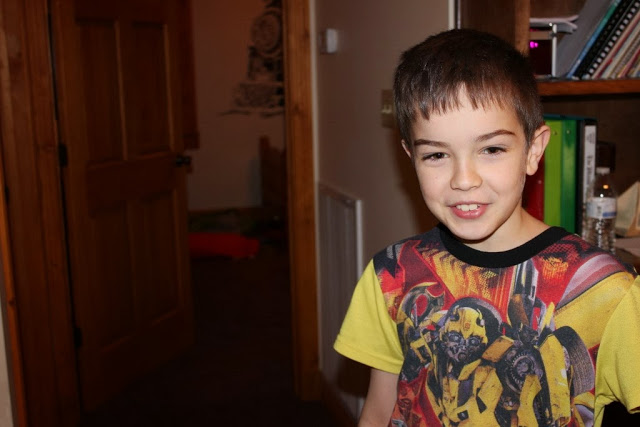

In an effort to approach math from the perspective of promoting dialectic discussion, I intentionally asked questions of definition, comparison, and relationship as my oldest son struggled through some problems. Below is what it looked like to have him reason through the questions I was asking. As I asked questions, he asked more questions. It was contagious and enthralling! Can you see the excitement and revelation from this discussion?

To solve a math problem but also come up with a much deeper understanding was a thrill for him. During those moments we were a team struggling through mathematical ideas together. He (and I) absolutely loved it. I want to see these “shining eyes” each and every day! And with the Five Common Topics, I can train myself to ask these type of questions! There’s so much more I could say, but here are nine thoughts regarding the art of questioning.

- Share ah-ha moments with your children in whatever I am doing. Look for opportunities to ask questions as you go about your day.

- Remember that questions are more important than answers; the journey of discovery is more important than the discovery itself.

- Brainstorm with your child on the whiteboard when completing writing (or other) assignments. We use questions derived from IEW’s Story Sequence Chart: Who is the story about? What is the conflict/problem of the story? How (and when) is the conflict/problem resolved? What can we learn from this (and why is that important)?

- Ask questions of your child instead of correcting or marking his/her paper. Let him find his own mistakes by asking good, open-ended questions (e.g., ask questions with the intention of building bridges from one thought to another).

- Learn to be active readers. Model for and teach them to read with a pencil in hand. You might want to grab Mortimer Adler’s How to Read a Book.

- Ask good questions through games. {Games work for all ages and stages of learning!}

- Model an interest in writing by journaling or admiring the written work of others. (You can do the same with art, classical music, poetry, math – any subject!)

- Tension is okay – take a walk together to work through the tension of a question. Wrestling with questions is a good thing!

- Do not allow a fear of failure to hinder your questions. It’s okay to be incorrect. The goal of education is to give us a voice and to grow in wisdom. Without a teachable spirit, we block the growth God intends for us!

There is much to be learned about how to ask significant questions that help students (and self) to grow in knowledge and wisdom. Seize this beautiful opportunity as your children mature into adults! The more we ask and engage in dialogue with them, the more they will recognize their importance in our lives and in their world. Let us learn how to ask meaningful questions as we attempt to train our children in this lost tool of learning!